Art with no origin 2019

1

How can it be so that the term, ‘art’, makes sense in contexts that have nothing whatsoever to do with art?

What does it mean, for instance, when pundits speaking about the labour market refer to ‘artistic practice’ as a model for the implementation of self-realization and creativity as qualitative parameters for the working capacity of employees?

Or how is it possible to use ‘the artist’ as a vanguard in processes of gentrification, where artists and other bohemians are stimulated to live and work in rundown neighbourhoods that are supposed to be made attractive for investment and well-off citizens?

And what is ‘art’ doing in educational programmes for technological innovation and entrepreneurship?

These questions have many answers but they only make sense because the terms ‘art’, ‘artist’, and ‘artistic practice’ are unproblematically transferrable to contexts that have nothing to do with art. These questions do, in other words, indicate that ‘art’ is functioning as a term with common validity.

How is this possible? What does it mean when ‘art’, ‘artist’, and ‘artistic practice’ are used as social and cultural notions of common value?

One response to this question would propose that the usage of ‘art’ as a term with common validity entails that ‘art’ is an institution. A social and cultural institution. A mechanism that regulates social and cultural formation in general.

In this way, using the term, ‘art’, in the institutional sense signifies that ‘art’ is a social and cultural regularity. That art is always already there, regulating the lives we live. That art is an integrated part of social and cultural regulation as such.

2

To find out whether this approach to ‘art’ as an institution makes sense, I meet with the sociologist Lars Bo Kaspersen, to hear what he has to say.

Kaspersen agrees that institutions are indeed to be conceived of as regulating mechanisms. It is merely a question of the sense in which we are talking about regulation. He refers to the current ambiguity in the usage of the term, ‘institution’, within social and political sciences, calling this ‘a semantic battle field’; a fierce struggle regarding the signification of the concept ‘institution’ as represented by theoretical positions like neo-institutionalism, sociological institutionalism, and historical institutionalism.

We talk about how this ‘semantic battle field’ is somehow parallel to the apparent semantic meltdown in Western democracies where political agency is often characterized by ambiguity and self-contradiction, as when prospects of de-regulation go hand in hand with a legislation that increases state regulation.

To Kaspersen, this particular instance of contradiction is essential to gaining an understanding of the agency of neoliberalism. As he sees it, traditional liberalism was an ideological rebellion, equivalent to Marxism in that sense, and therefore unable to govern, whereas the neo-liberal agenda is characterized by the aim of neutralising current modes of regulation in order to install a new format of regulation that is all about government. As a result, state power is increasing and being executed ever more ruthlessly. Offering a relevant example, Kaspersen refers to the recent reform of the Danish university system that has turned educational institutions into political instruments, mainly for employment policies.

We talk about the role of ‘art’ within the social and cultural situation that Kaspersen outlines. By comparing the materiality of art with the symbolic representation of art, this sense of ambiguity and self-contradiction is only amplified.

We find that contemporary art is increasingly dominated by art works with a materiality equivalent to that of the film industry. We observe that the production of art works is extensively commission-based, i.e. ordered and financed by collectors, art institutions, and other investors, just as the actual realization of art works tends to be managed by studios or workshops that handle everything from conceptualization to execution and mediation. And we notice that the very same art works are being represented by a symbolic narrative, telling us that the artist is a singular originator of unique art works. And we witness a global distribution, consumption, and economy of art without precedent.

Realizing that the topic of institutional regulation is far from exhausted, our conversation is placed on ‘pause’ … to be continued, with Kaspersen pointing at the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann’s theory of Social Systems as yet another perspective to take into consideration.

Inspired by biology and cybernetics, Luhmann defines a society as the totality of a multitude of self-generative social systems. It is these systems that communicate, not humans. And each system is based on a binary code. For instance, the Art System is based on the code ‘beautiful/not-beautiful’, whereas the Political System runs on the code ‘power/not-power’. When the systems communicate, these binary codes are adapted to one another. In the Political System, the code ‘beautiful/not-beautiful’ is thus conceived according to the code ‘power/not-power’ while, conversely, the Art System adapts the code ‘power/not-power’ to the code ‘beautiful/not-beautiful’.

3

How did art become a social and cultural institution? At what point in history did ‘art’ emerge as a notion of common value and as a mechanism of social and cultural regulation?

One precondition decisive to the institutionalization of art must be the ability to conceive of art as something in itself. As a concept. And as a social and cultural materiality. Thus, on the one hand, the institutionalization of art has to do with the historical emergence of the autonomous category, ‘art’, and, on the other hand, with a specialization of art’s materiality.

In a Western context, the institutionalization of art takes place within a historical process that saw the constitution of art history and art theory being melded pari passu with the establishment of art academies and public art collections. None of these factors would make sense without the autonomous category, ‘art’. All these factors transform known quantities by means of ‘art’ as an autonomous category.

This is what happened in the 18th century: during the era of Enlightenment, of rococo and of a fundamental change in epistemology, men and women began to conceive of themselves as the creators and organizers of knowledge.

As it happened, the status of an artist began to change from that of a craftsman to that of an author. The commission-based production of art works managed by artists’ workshops was challenged by artists working individually and deciding motif, technique, and style on their own. The training of artists was gradually relocated from the workshop to the art

academies. The significance of ‘the artist’ became that of an origin. A creator. An author.

This is one historical process where it is pointless to speak of cause and effect. Too much was happening at one and the same time. It is important, rather, to notice that the conceptions of ‘art’ as an institution, ’artist’ as an origin, and ‘artistic practice’ as authorship are parts of the same historical process. Transpiring together with the establishment of art academies and public art collections. Entangled with the constitution of art theory and art history.

In this line of thinking, the status of an artist is never exact but evolves within a certain social and cultural habitat. Thus, the historical shift from craftsmanship to authorship will inevitably lead to further mutation of ‘the artist’. And a status not yet known is going to replace that of authorship. In all likelihood, it already has. We’re just not able to recognize art with no origin.

Money Dances

Jessica Diamond

1993

Transmutation of Species

Charles Darwin

1836

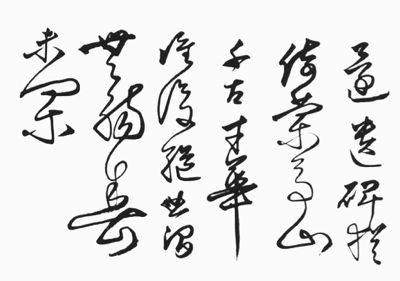

Song of the Cursive Script

Chang Pi

1460